How Does the Gut-Brain Axis Work?

Psychobiotics are microbes that talk to your brain. Here’s how.

Last week I talked about how psychobiotics are revolutionizing psychiatry. Psychobiotics are microbes that can improve your mood via the gut-brain axis. They can improve depression, anxiety, memory, and cognition. There’s even evidence that psychobiotics can help prevent Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s.

Although much more research needs to be done, there are some good theories about how microbes manage to pull off such a feat. One tantalizing clue is that if you cut the vagus nerve that connects the gut to the brain, many of the psychobiotic effects disappear – implying that at least some of the psychoactive properties of microbes are transmitted by that meandering nerve bundle.

Shockingly, bacteria know how to make neurotransmitters all on their own. Microbes don’t have brains, of course, but they may use neurotransmitters like dopamine and serotonin to communicate with each other, just like neurons do. They may be communicating with us as well. There is accumulating evidence that microbes could even be using these chemicals to affect our cravings, a spooky instance of mind control.

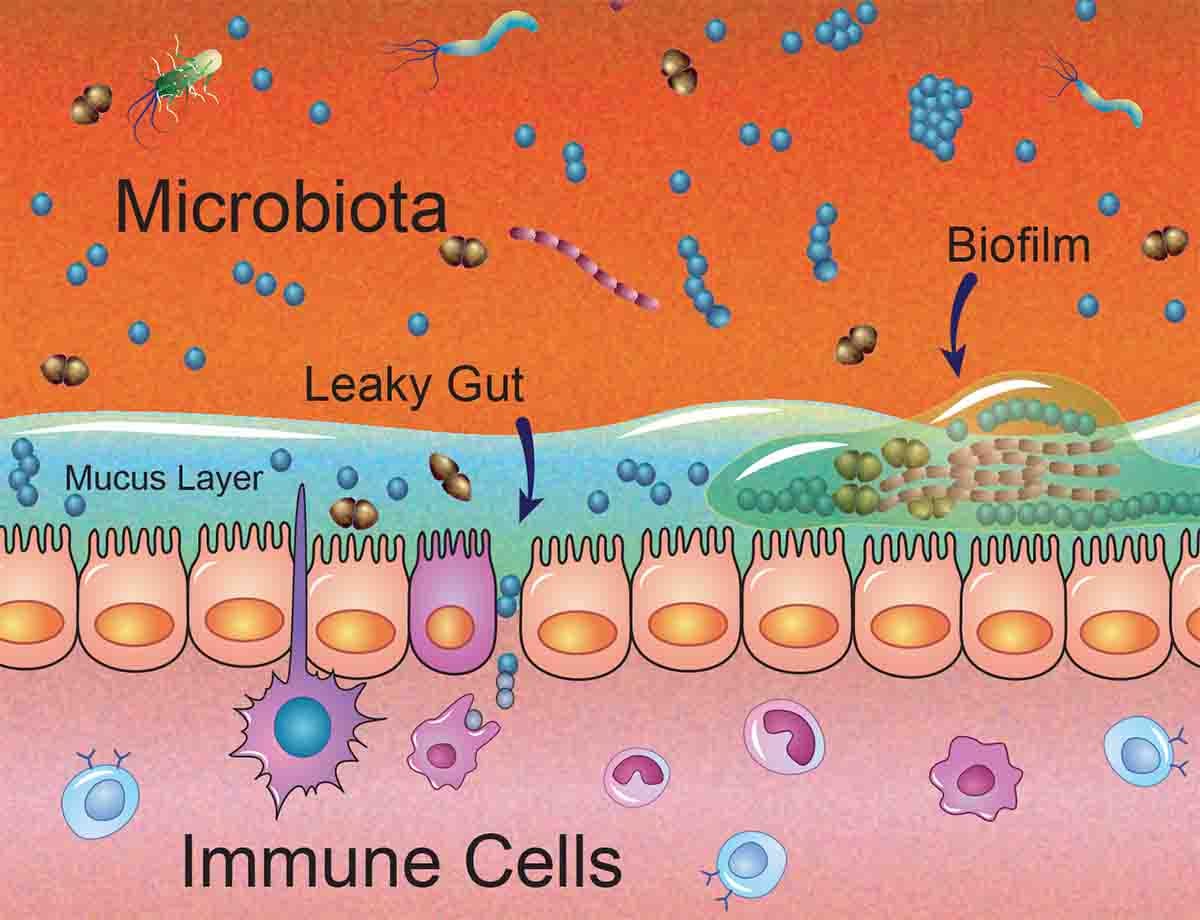

Leaky Gut

Perhaps the most powerful theory is related to so-called “leaky gut”. When your gut microbes are unbalanced, certain pathogenic (disease-causing) bacteria can dominate and they can be tenacious. Bacteria and fungi can build tough little microbial communities called biofilms. They are inhabited by many different microbial species, complete with microbial versions of foundations, plumbing, roads and electrical wiring. It’s hard to kill a biofilm because it is cemented together with a resilient gooey polymer. Like a tiny plant, it can flower and disperse “seeds” that colonize a new biofilm wherever they land. Some biofilms may be fine, if they produce helpful metabolites like butyrate.

But pathogenic biofilms may perforate the delicate gut membrane, allowing toxins and bacteria to enter your bloodstream. No matter how beneficial microbes may be in your gut, they are not meant to travel through your blood. Dutifully, your heart pumps these pathogens to every organ in your body, including your brain.

Leaky guts can lead to systemic inflammation, with bad results all around. Scientists believe that almost all chronic diseases start with inflammation, so this is not a small problem. One of the things that happens with systemic inflammation is that you become moody. Anxiety and depression are common comorbidities of intestinal diseases like IBS, IBD, Crohn’s, and celiac.

That’s because your brain is exquisitely sensitive to inflammation. If someone injects you with a tiny bit of LPS (a derivative of pathogenic bacteria), you will immediately become acutely anxious. Anxiety is your mind’s way of alerting you to an infection. Inflammation can lead to psychosis as well: hepatic encephalopathy – a liver inflammation – can cause psychotic behavior, personality changes and hallucinations. We know it is caused by bacteria because it can be cured by antibiotics.

However, studies show that psychobiotics can improve the mood of even healthy individuals, implying that inflammation may not be the whole story. More research is needed to fill in the gaps in our understanding, but the field is moving quickly. I’ll cover more of the mechanics of the gut-brain axis in the weeks to come.

Can we control our microbes to improve our mood?

The research so far has indicated that healing a leaky gut can go a long way toward improving mood. The best way to do that is to support psychobiotics such as Bifidobacteria longum, Lactobacillus rhamnosus, and Akkermansia muciniphila that nourish the gut lining. How do you support them? That turns out to be fairly easy: increase your consumption of fiber and ferments.

Fiber refers to chains of sugar molecules that our body can’t break down, but our microbes can. Properly fed, these beneficial microbes produce substances like butyrate that are excellent gut salves.

Fiber is found in veggies and fruit, two food categories that have dropped precipitously from western diets. Vegetables like artichokes, asparagus, onions, garlic, and beans are full of fiber. So are fruits like berries. An important source of psychobiotics is fermented food like sauerkraut, pickles and yogurt (unsweetened).

Refined sugar and junk food, on the other hand, support pathogenic microbes that may lead to leakiness.

The bottom line

Not all psychological problems start in the gut, and some amount of depression and anxiety is normal and healthy. For those with long-term depression, antidepressants are still popular and effective tools. Still, a psychobiotic alternative has great promise as an adjunct to psychoactive drugs with no known side effects (outside of a little gas).

The beauty is that you can try fiber or ferments yourself with a trip to the grocery store. Psychobiotics are complex, involving all bodily systems, and everyone is different due to unique genes, environments, diets and antibiotic history. So, pay attention to your psychobiotic adventures and take notes about what works for you.

If you are already being treated by a psychiatrist, make sure to talk to them about diet changes. But even if you are already on a drug regimen, keeping your gut in good shape can’t hurt.

If you are a psychiatrist, the lesson of psychobiotics is that it might be wise to check on your patient’s gut as well as their mind. As strange as it seems, microbes affect your moods, and simply eating better could change your life.

In the coming weeks, I’ll talk about specific steps you can take to improve your gut microbes and optimize your mood and cognition. Stay tuned!